| Citizen Dog (Wisit Sasanatieng) 35 Drawing Restraint 9 (Matthew Barney) 75 U-Carmen eKhayelitsha (Mark Dornford-May) 61 |

Saturday, September 17, 2005

Ratings Update:

Free Zone (Amos Gitai)

Free Zone (Amos Gitai) 52 – Content-wise, this vision of a hopelessly divided Mid-East is didactic and oversimplified. Through Gitai’s style, it becomes somewhat improved. Starting with a seemingly indulgent 10-minute single shot of star Natalie Portman as she cries and listens to a song that asks bluntly, “How long will this circle of horror last?”, Free Zone turns out to be a surprisingly tense tale of border-crossing, both physical and psychological.

Portman is slightly (intentionally) annoying as an American who imposes upon her female Israeli driver (improbable Cannes prizewinner Hannah Laslow), a woman who must travel to the tax-free zone between Jordan and Saudi Arabia to pick up a cash payment after a bomb injures her husband. The backstories of both women are interesting (especially the scene in which Hannah explains that she and her husband sell armored cars instead of flowers because they found war to be the only certainty in their lives), and the film uses a layering of images to suggest that the characters are haunted by their pasts as they experience the present. It’s a sharp movie that only begins to stumble once the women reach their destination, and meet a third woman, Leila (Hiam Abbass), who is in a predicament as dire as either of theirs. Gitai’s lack of political subtlety gets even worse when Hannah and Leila begin bickering about the payment of the cash. One suspects that he thinks he’s giving us a fair-minded portrayal here, but because Leila’s immediately thrust into the conflict and not given the same stylistic treatment as her backstory is relayed, it feels lopsided. The ending, which admittedly provides a rhyme to the opening shot, is too simple too be taken very seriously.

Rating update: Time to Leave (Le Temps qui reste) (Francois Ozon) 43

Look Both Ways (Sarah Watt)

Look Both Ways (Sarah Watt) 36 – This sub-Magnolia ensemble piece is too contrived to really work. Centering on a train wreck that left a man killed, the movie improbably presents the event as a central opportunity for soul-searching in its entire sad sack cast. Without much in the way of originality, it features disconnected characters trying to overcome themselves as they tentatively work toward emotional bonds. It’s been done a million times before, and usually been done better. The catharsis, when it finally comes, feels awfully forced because the initial crisis felt so forced.

Stylistically, Watt shows mild promise. This is her first feature film, following a series of animated shorts. That background makes itself apparent in frequent, short animated scenes that show her lead heroine’s daydreams. Her leading male character, a photographer, similarly has his interior anxieties conveyed through brief, rapid-fire photomontages. When their inevitable sex scene occurs, Watt crosscuts it with snippets of both of their interior apprehensions, resulting in a flurry of anxiety. Unfortunately, few scenes are so inspired. The culmination in particular feels like a direct rip-off of Magnolia. With a sub-Mann folkie warbling on the soundtrack, Watt crosscuts from one character’s low point to another, trying to make us understand the frustrations of coping with the world. It should be a powerful moment, but the near-lack of connection with these characters completely nullifies it.

Romance & Cigarettes (John Turturro)

Romance & Cigarettes (John Turturro) 51 – Not entirely, or even usually, successful, John Turturro’s Romance & Cigarettes is certainly a movie that’s unafraid to put itself out there. Filled with a lot of dialogue that’s either dirty talk or spoken song lyrics, the movie uses its (slightly incongruous) all-star cast to tell a story of disappointed, working-class aspirations. Turturro’s ambitions do slightly get the better of him. He’s trying to show adulterous behavior as part of a masculine, cyclic pattern and is additionally trying to lament the failed promise of the American dream.

Characters constantly make reference to celebrities from the old Hollywood star system, suggesting that the time they still had hopes has long passed. When the movie turns into a musical, it does so with a purposeful artlessness, as if these people come up short even while fantasizing. Only negligibly a musical-comedy, the movie is unafraid to take itself seriously. It doesn’t quite pack the punch that it thinks it does (it’s definitely, no Dancer in the Dark) but it’s a perfectly respectable failure. Kate Winslet is absolutely fearless here, in her best role in years. As the outright pornographic Tula, she owns every scene that she’s in.

Day 9 Ratings

Vers Le Sud (Laurent Cantet) 32

Everlasting Regret (Stanley Kwan) 26

The Notorious Bettie Page (Mary Harron) 31

In His Hands (Entre ses mains) (Anne Fontaine) 37

Brothers of the Head (Keith Fulton, Louis Pepe) 49

Friday, September 16, 2005

A few more ratings....

Look Both Ways (Sarah Watt) 36

Free Zone (Amos Gitai) 52

Runaway (Tim McCann) 33

Angel (Jim McKay) 38

The Great Yokai War (Takashi Miike) 62

Thursday, September 15, 2005

Iron Island (Mohammad Rasoulof)

Iron Island (Mohammad Rasoulof) 73 - Even though it’s set in a locale that would make Werner Herzog envious, Iron Island has more going for it than its setting. Following a group of Iranian squatters that have taken residence aboard an abandoned oil tanker, the movie examines the fascinating community that has been established and chronicles the end of their distinct way of life. Lorded over by Captain Nemat, an unforgettable personality who has dictatorial power over his minions (many who are presented in a way that maximizes the movie’s symbolic impact), the ship is filled with displaced individuals who give him total control. It’s not a sustainable way of life, though, as the ship is not only sinking, but has also been sold to a company that plans to turn it into scrap metal.

I haven’t seen Rasoulof’s debut feature, but this seems the emergence of an exciting new figure in Iranian cinema. Paced with none of the longueurs that usually dominate the country’s movies, it is as approachable a film as the country has produced. The love story had me worrying at the start, but it and the main plot dovetail in the film’s final reel, making a powerful statement about the constraints of society. This is a one-of-a-kind film, as fascinating in its execution as it sounds in concept.

Fateless (Lajos Koltai)

Fateless (Lajos Koltai) 33 – This Holocaust drama concentrates on the suffering of a young Hungarian boy, but seems more a showcase for cinematographer-cum-director Koltai’s photography than anything. Starting out interestingly, the film appears to be a spiritual inquisition into what it is that makes a Jew a Jew. Once the boy is transferred to the first of a series of internment camps, however, it becomes almost wordless, presenting a series of stylized images of the boy’s downward progression with next to no characterization.

Through voiceover narration, the boy tells the audience that he has reached a point where he’s accepted the fact that he might be killed at any time. For the longest time, there’s little emotional progression from that state, and the endless procession of non-dramatic, bloodless images of suffering becomes almost fashionable in its monochrome abstraction. Ultimately, the film seems to argue that the Jewish experience is one of suppression of response and resignation to fate, no matter what the circumstance, which makes the ending, in which the boy who has lived up to this questionable ideal rejects Judaism, all the more baffling (unless that hint that life goes on in the closing shot is meant to be a reaffirmation of lapsed faith…). While the film’s near-inability to articulate the experience makes it somewhat singular, its images are not any more striking than those in any other Holocaust film, which makes its pretentious inadequacies feel like a lapse of good taste.

Festival (Annie Griffin)

Festival (Annie Griffin) 49 – Set during the frenzy of self-promotion that is the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, this tonally shifting ensemble piece lapses out of control from time to time. It starts out by tartly introducing its characters, treating their theatrical endeavors with not a little skepticism. It stays bitter throughout, but from time to time asks the audience to get caught up in a budding romance, and the juxtaposition doesn’t quite work. Less successful still is the subplot that shows what happens when one actor’s demons stop being confined to the stage.

This sour approach works to an extent, and if it was pulled off, it certainly would have been more interesting than feel-good inanity. As is, this brand of wide-ranging satire is probably best left to masters like Altman. The difference between Altman’s best films and Griffin’s is that in his you believe the scenes continue after the scene ends. Here, the script plays out like a series of skits, dampening the impression that we’re watching real people (which is very real in the moments when the characters set off epiphanies in one another). Lucy Punch, who plays a sycophant comedienne with sass and self-interest, is the clear standout among the cast.

Tideland (Terry Gilliam)

Tideland (Terry Gilliam) 69 – I’ve got no clue how Tideland picked up such deadly buzz at the festival (and there were scads of walkouts at my screening…), but to me it’s an infinitely superior film to Gilliam’s recent fiasco The Brothers Grimm. Far more personal than that over-caffeinated bombast, this modern-day fairy tale is a great and distinctive work. Gilliam’s gift for invention is as present as ever here, and what I saw was, counter to what I had been led to expect, much more low-key than Gilliam’s work usually is (it’s certainly no Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in its directorial aggression factor).

One of the most impressive things here is the way the film’s fantasy sequences feel a part of a continuum. Even the most elaborate of effects sequences here (such as a scene in which a house becomes submerged in water) fail to overpower the rest of the film’s mood, and as a result don’t feel like standalone set pieces. Because of this, the film captures the flow of its pre-teen heroine’s imagination in a way that few films manage, flowing into an alternate consciousness that reality keeps sneaking into.

The film is loaded with the sort of obvious symbolism that gives meanings to our fairy tales and the uniqueness of its distinctly American, folkloric imagery conjures a distinctly Midwestern madness. Recalling Northfork at times, but operating on a higher level, the movie is unafraid to probe uncomfortable territory, plunging headlong into fantasies involving sex and death. This is all the more surprising given the story’s roots in a child’s mind, but Gilliam’s willingness to go there gives the movie its considerable emotional depth (the ending is nothing less than beautiful). Editorially, it unfurls at its own distinct rate, though I sort of suspect that what seemed to be pacing issues on my first look will feel a lot more natural when I see the movie again.

Walk the Line (James Mangold)

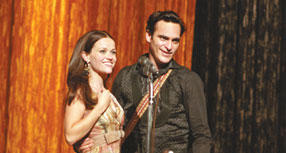

Walk the Line (James Mangold) 54 – I’ll start with the inevitable comparisons to Ray (which is inferior, despite it’s slightly higher rating) and keep this one nice and simple:

- Mangold is a much subtler director than Hackford, and even if both movies are pop crowd-pleasers, I’d have to give Walk the Line the edge. It’s first two and last two minutes are especially good.

- Ray was certainly a solidly acted movie, but Phoenix is easily more impressive as Johnny Cash than Foxx was as Charles. The lack of lip-syncing certainly makes a difference here, and the fact that Phoenix doesn’t have to fake blindness makes his performance feel like less of a stunt. By the time he was cutting his first record, I believed Phoenix completely in the role.

- Witherspoon is better still as June Carter Cash. Using every bit of her spunkiness, she gives an exceptionally good performance, given the script that she has to work with. I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that more of her screen time is spent singing than not (she and Phoenix share at least a half-dozen duets throughout the course of the story), and her voice is distinctly hers but completely believable as a country star’s.

- When Phoenix and Witherspoon get together, sparks fly. Oscar nominations for both are inevitable and probably deserved. The duo has what will likely be the best movie star chemistry of the year, and they create it despite playing characters that feel like normal folks first and celebrities second.

- That’s one of Walk the Line’s biggest problems. Perhaps trying too hard to make its stars feel like common people, it ends up relegating both the singers’ creative process and the factors that made Cash so musically significant to the sidelines

- Worse still are the biopic clichés that define Cash’s tendencies in pop psychology terms. His dead brother and bitter father are shortcuts to proper characterization no matter how based in fact they might be. When the third act crisis of Cash’s dug addiction takes center stage, and his inevitable recovery looms, there’s next to no dramatic tension because we’ve been there so many times before.

- Every single one of the musical sequences is a highlight. On this front, the movie is stellar.

Duelist (Lee Myung-se)

Duelist (Lee Myung-se) 28 – I haven’t seen Nowhere to Run, the film that made Lee’s reputation in the States, but now I’m dying to check it out just to see what the fuck happened. A frenzy of garish, misapplied style, this period action film seems the work of a stylist that simply piles on style without much regard for meaning. A perfect example comes on early in the film when a chase through a marketplace causes a bag of money to be dropped on the ground. Lee shoots the frantic chase for cash that follows in extreme slow motion, extending a completely subsidiary bit of the story for an eternity.

That’s not to imply that there’s much story to be found elsewhere. The plot, which concerns a hunt for counterfeiters, is about as generic as it gets. The characterizations are as erratic as Lee’s visual style, ensuring the movie has no emotional impact whatsoever. The performers use the exaggerated motions and loud voices of characters found in an American animated film, much to my chagrin. The film’s lone highlight is a fight scene shot in a space that’s half cloaked in complete darkness. The flashes of that battle that we see are more exciting that the rest of the film’s clashes combined.

Why We Fight (Eugene Jarecki)

Why We Fight (Eugene Jarecki) 53 – This political doc examines the reasons the United States is in Iraq, and does some stuff remarkably right. It’s decidedly non-partisan, wisely suggesting that people place blame for the conflict not on President Bush, but instead on the system itself, which is consistent in its warmongering tendencies, no matter who’s in the Oval Office. Starting with Ike’s farewell speech, in which the ex-President coined the term “military-industrial complex”, the movie examines that term and begins to trace how the United States’ interests have shifted so they have less to do with Democracy than with Imperialism.

Less concerned with inciting the audience than informing them, Jarecki largely resists the finger-pointing that dominated Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 911 (I only wish that a movie this much smarter than that one could be the subject of such a fierce public debate!). Jarecki’s stunts are smaller in scale and doubly effective than Moore’s. One scene in which he shows that a man’s request to have his dead son’s name put on a bomb required the approval of forty-something parties demonstrates the sprawl of our nation’s military empire. Another scene in which Senator McCain badmouths Vice-President Cheney and then immediately receives a call from him is a serendipitous display of the self-protecting powers that be that Jarecki had been talking about until that point.

The film’s greatest problem is actually the fact that its capably relayed thesis is essentially common knowledge to anyone who is able to read between the lines of the news that we see. Obviously, not every viewer needs to have this aspect of American motivation explained to them, so much of the film’s shock will feel beside the point. Nonetheless, fans of political documentaries have plenty to be excited about here, though the fact that this up-to-date film won’t be commercially released until next year might hamper its timeliness among first time viewers.

Backstage (Emmanuelle Bercot)

Backstage (Emmanuelle Bercot) 63 – Locking its sights on obsessive behavior, Backstage feels almost like All About Eve as re-imagined by Clare Denis (Denis’ frequent collaborator Agnes Godard shot it to boot). The film starts on an exceptionally high note with a scene that turns a reality show meeting with a teen girl’s celebrity idol into a harrowing and uncomfortable study in inappropriate awkwardness. Following that fiasco, Lucie, the embarrassed girl, improbably makes her way into her object of obsession’s inner circle, prompting a complicated emotional journey that reveals a several strikingly destructive cases of codependence.

Bercot slightly loses her control in the second hour, as the protagonist becomes more aggressive in her plotting. The film, which seemed to power on infatuation and instinct early on, becomes more conventionally plotted, which is disappointing, even if it never exactly nosedives. Throughout, the director refuses to take the easy way out of a confrontation, always making the audience squirm before she ends a scene of conflict. It’s an intelligent approach that leaves few motivational questions unanswered in a film chock full of complexly layered (and impressively performed) roles. Clearly, Bercot is a director to watch.

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (Tommy Lee Jones)

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (Tommy Lee Jones) 47 - I have no idea what Roger Ebert, who says this is his favorite film from the last several years, sees in this relatively slight moral tale. Midway through, a companion of mine compared the onscreen action to an episode of HBO’s “Six Feet Under” and even though the association’s not perfect (it similarly combines gallows humor with moral transgressions before dawdling into themes of forgiveness), it’s too close for comfort, especially since the average episode of the TV show offers more to chew on! Equally puzzling is the Cannes Jury’s decision to give the Best Actor award to star Tommy Lee Jones, who doesn’t do anything remotely interesting here, and certainly doesn’t perform an Eastwood-style investigation into his screen persona.

The same dopey selectively omniscient perspective is in effect here as in screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga’s 21 Grams with pretty much the same pitfall. In an attempt to alert the audience to both the frustrations of an unsolved mystery and the guilt of knowing the unspeakable truth, the same key scene is repeated several times, utterly diluting its impact. Not much else fills the void, I’m afraid, leaving the viewer with a story that constantly strains for significance but ends up shooting itself in the foot with its bland, self-consciously rounded characterizations (Americans are confused while Mexicans have a firm sense of self and justice) and hopelessly contrived plot. One aspect of the script that did work for me was the ever-present body of Melquiades, which serves as a constant reminder that the arduous journey taken in the film’s second half has little to do with corporeal concerns. The end result is watchable enough, even if it’s not in any way profound.

Bangkok Loco (Pornchai Hongrattanaporn)

Bangkok Loco (Pornchai Hongrattanaporn) 30 – The “WTF?” factor is high in this Thai flick’s genuinely zany first few minutes. Starting out with the feel of a live-action cartoon, this film kicks off with a cascade of ‘70s pop kitsch. For a while, everything, from the narration (presented with an accompanying Star Wars-style font) to the credits (which are not only presented as digetic objects as the characters run through a marketplace, but are still present when the location is later revisited) comes fast, funny and cheap.

It slows down, quickly, though, settling into a plot involving “The Drums of the Gods”, which is a magical instrument that can be wielded by the forces of good and evil. A silly conflict between the two forces ensues, with a naive couple representing the forces of good and Ringo Starr (!) fronting for the bad guys. It’s as silly as it probably sounds and as insubstantial as you might fear. Interminable song sequences and a bunch of stupid sex comedy dominate the rest of the run time.

River Queen (Vincent Ward)

River Queen (Vincent Ward) 39 – There’s an impressive budget behind this New Zeland-set war film, and it’s all put up on screen. Unfortunately, it’s somewhat lacking in its cohesiveness. A completely exhausting narration (provided by star Samantha Morton) attempts to compensate for the fact that the movie is trying to cover way more ground than it should in so brief a runtime. Telling the story of an Irish woman who heads into hostile territory to find her kidnapped half-Maori son, the film has an incredible amount of narrative incident. Morton is to be commended for making emotional sense out of a character whose complex motivations change constantly. She’s the closest thing to an anchor that this hopelessly adrift movie has.

Ward is an intelligent director who tends to nonetheless make major slip ups in his films. Here he fully resists turning the Maori people into noble savages (their chief is a womanizer, for example) and resists moments of heroism in his battle sequences, only to indulge in some seriously stale chick flick clichés. The whole movie seems too tightly centered on its protagonist’s point of view to achieve the epic feel that’s being attempted.

Wassup Rockers (Larry Clark)

Wassup Rockers (Larry Clark) 60 – To simply describe Wassup Rockers as an L.A. version of Clark’s Kids would belie its lighter tone and better-developed sense of humor. Not at all a cautionary tale aimed at negligent parents, Rockers is a casually observed road movie that sees a group of 13 to 16-year-old Latino boys from South Central venture into the precarious terrain of Beverly Hills.

Beginning with a series of near-verite scenes in which Clark helps us get to know his likable cast, the movie casually picks up significance as it develops into a full-fledged adventure. Too informal to be a true coming-of-age, this plot moves forward with an active disregard of consequence, grounding its come-what-may attitude in its central characters. Murders and deflowerings are treated with the same nonchalance as the prevalent class issues. The wildly exaggerated behavior of the characters in Beverly Hills suggest that we’re getting a skewed perspective, but perhaps it’s because the movie so well captures the teens’ point of view that it’s so fun to watch.

One disappointment is the muddy video imagery, which belies Clark’s background as a photographer.

Wednesday, September 14, 2005

A few more ratings....

Backstage (Emmanuelle Bercot) 63

Why We Fight (Eugene Jarecki) 53

Duelist (Lee Myung-se) 28

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

Cache (Hidden) (Michael Haneke)

Cache (Hidden) (Michael Haneke) 68 – Micheal Haneke’s latest film is a superb piece of work, made by a master of the form, yet I’m not quite sure how much I actually like it (that rating’s pretty arbitrary, really…). By design, it’s a purposely-unsatisfying contraption, centered on the French public’s (and government’s) denial of the Algiers atrocities. Beginning with a relatively standard thriller setup (a family receives a mysterious videotape of their own home in the mail with no idea who made it), the director crafts a vicious attack on bourgeois complacency, which he suggests is founded on denial of any political and personal unpleasantness.

There’s a great scene in this film where Auteuil tells Binoche that he’s been withholding information about his suspicions about who the perpetrator might be because he didn’t want to upset her. In another scene, the protagonist’s mother doesn’t wish to relive an unpleasant memory. This theme builds gradually, culminating in an ending that sees that sense of calm upended. Appropriately leaving you stranded with a “need to know” that you didn’t posses at the film’s start, it's a great frustration. Some people have offered hints about the meaning of the final shot, or the identity of a mysterious character that is glimpsed throughout, but since we’re not even certain whether that last shot is being shot from the stalker’s or the director’s camera (a brilliant move by Haneke that creates the paranoia that the protagonists is being watched in each scene), these bits of information only open more lines of questioning.

The brilliant script keeps the audience guessing, deriving its meaning from that open-ended process. Haneke’s method is to use the audience’s knowledge of generic conventions against them in order to create an expectation in the viewer that is never fulfilled. The tantalizing hints that the director gives throughout only further stoke our determination to solve a mystery that may not even have a solution within the film. The movie doesn’t just retard our desires for narrative resolution. It assaults the audience’s sense of entitlement regarding justice.

Ratings Only:

Wassup Rockers (Larry Clark) - 60

River Queen (Vincent Ward) - 39

Bangkok Loco (Pornchai Hongrattanaporn) - 30

Revolver (Guy Ritchie)

Revolver (Guy Ritchie) 47 – Run for the hills! Guy Ritchie has tried to make an art film!

This one gets excruciatingly bad in its last twenty minutes or so, as this essentially mindless movie tries to play mind games with its audience, but before that it’s enough of a typically entertaining Guy Ritchie film to still be somewhat redeemed. The director’s bold visual style turns this tale of a drug deal gone wrong into a ridiculously operatic, frequently funny series of skits featuring character actors that gladly chew the scenery for us.

Featuring Jason Statham once again, it finds Ritchie on familiar ground, and on a scene-by-scene basis, it does work well enough. The script, taken as a whole, is indisputably awful, though. It’s a puzzle movie with a few missing pieces. That doesn’t mean that one should ignore its strong compositional sensibility or fail to savor its winking tough-guy attitude. I’m sure I’m foolishly overrating this one as a whole (goodness, does it ever get bad...!), but I can’t help but take into account the amount of sporadic fun that I had with it. It probably helps that I can't follow the plots in heist movies half the time, even when I'm assured that they do make sense.

Isolation (Billy O'Brien)

Isolation (Billy O'Brien) 42 – The glib “Alien-on-a-dairy-farm” description that I’d been hearing to describe this bit of Mad Cow unease turns out to be pretty accurate, which isn’t to imply that this is totally unimaginative. It has a few great freak-out scenes near the start, in which the bulk of the terror emanates from a cow’s vagina (replete with shots from a vagina-cam!), but it’s a moodier, more deliberately paced piece than that beginning would have you believe. As it continues to up the gore ante, it prompted plenty of walkouts, culminating on a visceral autopsy on a baby calf that had people streaming away before it got any worse.

Isolation (Billy O'Brien) 42 – The glib “Alien-on-a-dairy-farm” description that I’d been hearing to describe this bit of Mad Cow unease turns out to be pretty accurate, which isn’t to imply that this is totally unimaginative. It has a few great freak-out scenes near the start, in which the bulk of the terror emanates from a cow’s vagina (replete with shots from a vagina-cam!), but it’s a moodier, more deliberately paced piece than that beginning would have you believe. As it continues to up the gore ante, it prompted plenty of walkouts, culminating on a visceral autopsy on a baby calf that had people streaming away before it got any worse.Unfortunately for those who stayed, it really doesn’t great worse than that disgusting scene, becoming afterwards a more conventional monster movie, in which characters roam an enclosed space trying not to be killed by said monster. Alas, it lacks Ridley Scott’s visual sensibility, which means that’s not really enough to sustain a high level of interest. Its incredibly dirty sets begin to look the same after a while, and its cast never makes enough of an impression to inspire too much sympathy, with the exception of a somewhat fun mad scientist performance.

Mary (Abel Ferrara)

Mary (Abel Ferrara) 67 – A serious-minded film from Ferrara about the confusion and anxiety that mark a true inquisition into one’s faith, Mary certainly upends itself in its quest to capture that disquiet. After several allegorical movies that dealt with a character’s quest toward faith, her Ferrara grabs the bull by the horns and makes his most explicitly spiritual movie to date.

I especially like the way that during the film our attitude toward Binoche’s character shifts. At the film’s start, she’s playing Magdalene, the disciple who might have in fact been closest to Jesus, and immerses herself so thoroughly into the role that it prompts a serious questioning of her life’s meaning. Other characters, as well as the audience, consider her to be mad, but as the film progresses, her calm is restored, even if her normalcy is not, and her conviction becomes a source of solace when everything else seems to have gone insane. The movie stresses her assertion that the transformation into a spiritual being “takes courage.”

More than most religious films, Mary underlines the idea of pure devotion as a scary, all-consuming state to those who haven’t yet taken the plunge. That anxiety makes it the perfect response to the media frenzy that surrounded Mel Gibson’s movie last year. Ferrara’s aggressive style makes this fear palpable. I suppose this might be a work of style over substance with its dazzling, intense last half-hour the clear standout. Throughout, the director uses his typical scenes of random violence to prompt a search for meaning. With his usual theatrical lighting and his slightly dreamy backdrops, he intensifies the sense of rising theological doubt that clouds his protagonist’s mind. It’s a film that imparts a remarkable sense of importance to its characters’ spiritual progression to those viewers to shake its admittedly heavy hand.

Monday, September 12, 2005

The Forsaken Land (Vimukthi Jatasundara)

The Forsaken Land (Vimukthi Jatasundara) 52? – I had to walk out of this one to make my screening of Mary, so I missed the last five to ten minutes, but unless the film became impossibly good (which at least one person has assured me it does) I think this rating’s pretty close to the final one I’ll have when I get to catch that ending.

Set in an extremely remote section of Sri Lanka, this Cannes prizewinner examines the ways that its scattered residents cope with living in what might best be described as a wasteland. Laced throughout with remarkably evocative landscape photography, the movie constantly pauses to watch as characters cool themselves off with water or pause to feel a passing breeze. Whether by having furtive sex or trying to forget themselves by wandering around aimlessly, the characters are always trying to push away the anxiety that the war-torn environment causes. It’s a movie that focuses tightly on seemingly insignificant experience, and in doing so captures a state of mind that flourishes under this particular kind of pressure.

Ratings only for now:

Mary (Abel Ferrara) 67

Isolation (Billy O'Brien) 42

Sunday, September 11, 2005

Manderlay (Lars von Trier)

Manderlay (Lars von Trier) 74 – Practically nothing would have felt like a worthy successor to Dogville, but Manderlay is better than I had expected it to be after its mixed Cannes reception. In this movie, presented unmistakably as an allegory for the United States’ tendency to play big brother to “less fortunate” nations, Grace (played here by Bryce Dallas Howard, in a performance far inferior to Nicole Kidman’s Dogville turn) meddles in “a local matter” when she discovers a plantation still operating with slaves, seventy years after the abolition of slavery. The setup seems tough to swallow at first, since it lacks the damsel-in-distress factor that made Dogville so immediately gripping, but ultimately the story becomes involving.

Manderlay (Lars von Trier) 74 – Practically nothing would have felt like a worthy successor to Dogville, but Manderlay is better than I had expected it to be after its mixed Cannes reception. In this movie, presented unmistakably as an allegory for the United States’ tendency to play big brother to “less fortunate” nations, Grace (played here by Bryce Dallas Howard, in a performance far inferior to Nicole Kidman’s Dogville turn) meddles in “a local matter” when she discovers a plantation still operating with slaves, seventy years after the abolition of slavery. The setup seems tough to swallow at first, since it lacks the damsel-in-distress factor that made Dogville so immediately gripping, but ultimately the story becomes involving.

Trier’s sense of humor helps a lot here, and even though the narrative this time out is more straightforward than in Dogville and the shock quotient lower, the ending still reproaches liberal condescension with considerable punch. The snappier pacing is very noticeable, but it’s somewhat lamentable, too, since the characterizations tend to be less fully calculated to sting the liberal-minded viewer’s assumptions. Grace is the lone exception, here acting more as an individual with an agenda of her own than in Dogville, which seems to limit Manderlay’s overall ambiguity (even if her meddling is necessary for the central allegory to work).

Complaints, aside, it's an extremely solid, if less than astonishing, piece of work. Second-rate Dogville is still first-rate by any other rule, apparently.

3 Needles (Thom Fitzgerald)

3 Needles (Thom Fitzgerald) 65 – Fitzgerald’s last movie, the lamentable The Event, made me enter this one with fairly low expectations. What I got would have satisfied just about any expectations that I could have had, however. A sprawling trio of tales, 3 Needles presents AIDS as a worldwide crisis, examining the economic, social and regulatory issues that swirl around this very complex problem. It’s a movie that doesn’t attempt to offer solutions so much as it tries to acknowledge and put a human face on the myriad ways that the disease is causing suffering.

3 Needles (Thom Fitzgerald) 65 – Fitzgerald’s last movie, the lamentable The Event, made me enter this one with fairly low expectations. What I got would have satisfied just about any expectations that I could have had, however. A sprawling trio of tales, 3 Needles presents AIDS as a worldwide crisis, examining the economic, social and regulatory issues that swirl around this very complex problem. It’s a movie that doesn’t attempt to offer solutions so much as it tries to acknowledge and put a human face on the myriad ways that the disease is causing suffering. In none of the stories are we conventionally asked to feel sympathy for an AIDS patient. Fitzgerald already made The Event, I suppose, and doesn’t feel the need to retread that ground. Instead, the tales that we do get to see (just three out of ninety million, the narration tells us) seem designed to consider implications of the disease that we might not have yet considered and to examined the complex psychic toll that dealing with the disease can take. One story, set in Montreal, documents an outbreak of the virus in the porn industry. The dazzling African sequences are concerned less with the plights of the victims than the toll that it takes on the missionaries sent to help. The third plot, set in China, involves a shifty bloodbank’s operation, in a story that easily trumps the similarly themed The Constant Gardener. This might all sound depressive, but Fitzgerald doesn’t submerge us in the trauma. He holds back and presents the ordeal with clear-headed organization that only magnifies the film’s scope.

Thank You For Smoking (Jason Reitman)

Thank You For Smoking (Jason Reitman) 62 – This media-savvy satire stars Aaron Eckhart in a slimy and charismatic performance as a lead spokesperson for the conglomeration of cigarette companies. Though sometimes a bit too broad for its own good (some cheap jokes such as the funny acronyms that are bandied about don’t help matters), it’s usually funny enough to power the viewer past such complaints. Concerned primarily with the moral flexibility of its protagonist, the script does a good job of demonstrating that he’s just a cog in a machine filled with similarly unscrupulous individuals.

Thank You For Smoking (Jason Reitman) 62 – This media-savvy satire stars Aaron Eckhart in a slimy and charismatic performance as a lead spokesperson for the conglomeration of cigarette companies. Though sometimes a bit too broad for its own good (some cheap jokes such as the funny acronyms that are bandied about don’t help matters), it’s usually funny enough to power the viewer past such complaints. Concerned primarily with the moral flexibility of its protagonist, the script does a good job of demonstrating that he’s just a cog in a machine filled with similarly unscrupulous individuals.In the scene in which we see Eckhart teaching his son to bullshit his way through homework, which itself is on a bullshit, vague topic, the movie seems to be pointing directly at the acceptable decline in discourse that has made jobs like Eckhart’s character’s meaningless figureheads. Exchanging knowledge is far less important than winning the public opinion. Crucially, though, the movie never has the balls to challenge the lemming masses that accept easy rhetoric in public debate. As much as it pretends to be a take-no-prisoners satire, it feels an unnecessary impulse to please the audience when it should be directly insulting them. Thankfully, though, that impulse doesn’t lead to a complete retraction of the lead’s shady morality. Eckhart’s slimy grin and everything it represents remain after the dust-up has ended.

Sa-kwa (Kang Yi-Kwan)

Sa-kwa (Kang Yi-Kwan) 55 – This drama is refreshing because it starts out portraying everyday Korean life in a functional family that seems to genuinely like one another. When they embarrass one another, they do so in a minor, believable manner, as opposed to an exaggerated Meet the Parents-style fiasco. The degree to which these characters’ problems matter is made clear to us, but they aren’t wildly distorted for dramatic effect.

When the film chooses to focus on the relationship of Hyun-jung, the older daughter of the family, though, its sensitivity is somewhat reduced. Things get too touchy-feely as we’re given scene after scene in which characters are explaining why they acted as they did or why they feel as they do. The second hour of Sa-kwa grows tiresome as the indecisive girl weighs her options, but Moon So-ri is absolutely excellent in the pivotal role. Even as the movie drags on, she remains a vital presence on screen. Her transformation from the mischievous girl she is at the start of the film to the emotionally complicated woman that she ends up at the end is believable at every step.

Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee)

Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee) 71 - Amazingly, this infamous "gay cowboy movie" doesn't stumble at all in its portrayal of sexuality. It’s biggest failing is actually its own desire to cram twenty years of life and regret into two hours and ten minutes. As a result, it’s somewhat choppy and momentarily uninvolving. Immediately after the screening, I would have insisted that the movie was harmed by not being an hour or so longer (e,g, Anne Hathaway’s part is smaller than her character’s hair), but as I walked to my next screening, a curious thing happened, and the movie began unpacking itself in my mind, seeming richer and more subtle than I was giving it credit for. The last time this happened to me was with Million Dollar Baby, which I like drastically more upon my second viewing. Here’s to hoping that’s the case here as well.

In any instance, the comparisons between this film and The Age of Innocence are appropriate, but Lee’s style hangs back and goes for our head when Scorsese dives in, aiming for the heart. The movie is intelligent, with both passion and angst are represented with a bare minimum of fuss. Perhaps Lee should have been less afraid of having this turn into a soap opera, but there’s still nary a misstep here. Fascinating in its exploration of cowboy iconography (the brief moment where the two men are allowed to be emotionally fulfilled cowboys is a curious one, and I can’t think of many similar moments outside of Hawks), the movie crucially points out the fact that these men were outsiders before they were gay lovers.

Heath Ledger is awards-worthy here. The backdrops are so consistently stunning that they warrant use of the word vistas. The haunting closing image is absolutely perfect. Despite a massive degree of difficulty, Ang Lee delivers again.

Hell (L'Enfer) (Danis Tanovic)

Hell (L'Enfer) (Danis Tanovic) 34 - Shouldn't this have been Purgatory (of Kieslowski's projected trilogy of Heaven / Hell / Purgatory), given that most of its characters are stuck in a cycle of repeated self-torture, which eventually is lessened by a revelation? No matter, really, since it's such a resolutely stupid movie. Man-hating to the point of absurdity, it seems to leave plausibility behind in an attempt to be more fable-like, despite the fact that it claims classical tragedy is impossible in our modern, Godless society. Leaden symbolism clogs up the works and absurd plotting is meant to be excused when the film not only professes to be about some sort of hokum like coincidence or destiny, but also has a college professor explain the difference between the two! It's rather telling that the footage of birds in the opening credits delivers a more interesting psychodrama than what follows.

At least Emmanuelle Beart is solid...

Be With Me (Eric Khoo) 50 – Taking an original approach to the biopic, Eric Khoo’s Be With Me is a mixture of some truly fresh ideas and a few very tired ones. The opening credits inform the audience that the film has been adapted from the autobiography of Theresa Chan, but if not for that hint, you’d never guess that this boldly structured film had a single, non-fiction source until its midway point. For the first forty-five minutes of Be With Me, Ms. Chan is just one of a diverse set of characters who roam around Singapore, feeling generally disconnected from those they desire the most.

It’s become cliché to make an art house film these days about alienation, but by eventually bringing Ms. Chan’s story to the fore, he somewhat redeems that decision. Deaf and blind since the age of fourteen, Ms. Chan is an inspiring figure. We eventually see excepts from her autobiography, relayed to us only through subtitles, and soon come to understand how it is that she has reached out from her state to touch those around her. In practice, Khoo’s film becomes about our need to communicate; to share our stories and to relate to those of others. It’s disappointing, then, that the stories of those people that she touches aren’t more interesting. Though each of them is thematically relevant to the whole, they intersect with one another in unsatisfying ways, feeling like third-rate Tsai.

Banlieue 13 (District 13B) (Pierre Morel)

Banlieue 13 (District 13B) (Pierre Morel) 34 – This action film, set in the year 2010, takes place in a socially malfunctioned Paris, in which the poorer sections of the city have been walled up by the frustrated administration. Little in the way of social commentary is provided beyond that setup, however, since this is a film that’s far more concerned with ass-kicking than muckraking.

Banlieue 13 (District 13B) (Pierre Morel) 34 – This action film, set in the year 2010, takes place in a socially malfunctioned Paris, in which the poorer sections of the city have been walled up by the frustrated administration. Little in the way of social commentary is provided beyond that setup, however, since this is a film that’s far more concerned with ass-kicking than muckraking. As far as mindless action films though, you’re better off checking out last weekend’s truly absurd Transporter 2 than watching this. Despite some decent stuntwork, the fight choreography here fails to inspire. Rather than featuring a martial artist, the film stars one of the inventors of the French extreme sport parkour, in which participants find themselves climbing and jumping their way across city rooftops. That makes for exciting unscripted competition, I’m sure, but in a narrative film, it’s the equivalent of having a superhero movie in which the special power is the ability to run away really fast.

When the movie shifts midway into a buddy cop flick and the heroes are given twenty-four hours to find and defuse a bomb, the imagination level drops dramatically, and the futuristic setting all but ceases to matter. By no means a chore to watch, Banlieue 13 still fails to ever really excite.

October 17, 1961 (Alain Tasma)

October 17, 1961 (Alain Tasma) 35 – I’m not having much luck with my random slot fillers this year…

This dramatization of the French police response to the local FLN presence during the Algiers conflict fails to excite. Starting out, almost promisingly, as a French Bloody Sunday, it soon ditches its nervous handheld camerawork, bizarrely becoming less frenetic as the tensions rise. I’m not certain that this production was made for French television, but I wouldn’t at all be surprised to find out that that was the case.

Although there are sequences included to give the illusion of impartiality, it’s ultimately a thoroughly one-sided account of the affair. Its characterizations are facile. When one man asks his brother, who is studying furiously, in the opening moments, “Don’t you ever stop?” you know that you can count the man amongst the future victims. When the ordeal is over, it’s the account of a white woman that gets the most screen time, as if the filmmakers were already certain that the Algerian perspective had been adequately conveyed. It isn’t unfortunately, since the film is more interested in finger-pointing at bad cops.

Battle in Heaven (Carlos Reygadas)

Battle in Heaven (Carlos Reygadas) 60 – Maybe not the advancement over Japon that many hoped for, but still a singular piece of work, Carlos Reygadas’ second feature surveys the psychic damage that occurs after a kidnapping in Mexico City goes horribly wrong. The plot is a repudiation of those Paul Schrader-style films in which a sad sack works his way toward redemption. Here, Reygadas pessimistically concludes, neither legal nor spiritual justice can calm his working-class protagonist’s soul (and pitches the drama so that it implicates the director’s home country as well).

It’s clear that Reygadas is still developing his style. Some of his cribs (e.g. his Kiarostami-style in-car tracking shot, which is overlaid with a conversation) are even more distracting this time out, perhaps because this is a more cohesive work than the free-wheeling (though superior) Japon. Reygadas’ most distinctive gesture, the 360-degree pan is back here, sometimes used where it’s not really doing any good (I’m specifically thinking of that post-coital scene). His ambition is still incredible, and I’m willing to forgive him his missteps because he’s aiming so high. Serious-minded enough to command audience respect (even though it seemed mine disliked the film, there were very few walkouts), it’s filled with visionary moments that still alert the viewer of the brilliant career to come. Just when you thought you've seen enough art-film blow jobs to last a few lifetimes, here's one that transcends the cliche.

Saturday, September 10, 2005

Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien)

Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien) 77 – Not only is Hou Hsiao-hsien one of the directors who seems to best grasp how we live (and love) today, but he also has a pretty good idea about how we got here. The triptych of trysts, each featuring the same lead actors in different roles, outlined in Three Times are presented in tales entitled “A Time for Love”, “A Time for Freedom” and “A Time For Youth”. Like a Kieslowski trilogy rolled up into one movie, Three Times examines each of those themes in a way that politicizes the romances that we’re watching. The coy, mannered posing that we see in the 1960s-set “Love” seems perfectly natural, for example, until we have 2005 to compare it to. “Youth”, set in 2005, is a depressive tale (think Millennium Mambo without the benefit of the narrator’s hindsight), in which characters that have grown up with complete freedom to love and as a result love without pity or consequence.

To categorize modern love like this is certainly a broad statement (though no more broad than the statements made in the film’s other two time frames), but doing so thematically ties the three stories together and suggests we’ve grown detached from our own sense of history. As a result, the film almost feels reactionary, suggesting in some way that Taiwan’s freedom (which we hear about in the middle story, set on the eve of the country’s 1911 liberation from Japanese forces) has run amok, resulting in today’s societal malaise.

In any case, these three stories find Hou in a particularly sensuous mode, halfway between his mid-career master shot style and the more sensual groove of Millennium Mambo. The first third, in particular, is so stylistically charged that it will doubtlessly prompt comparisons to Wong Kar Wai’s work (I got a Scorsese vibe too), although it’s parallax compositions are distinctly the director’s own. The middle story, which sees Hou revisiting Flowers of Shanghai territory in a quasi-silent film (the score sometimes falls in sync with the action, but words are never spoken) suffers, primarily because it reveals just how intrinsic sound design is to Hou’s directorial vision. The final third, as I noted before feels almost like a quasi-sequel to Mambo though without that film’s liberating moments (even the motorcycle ride – a staple in Hou’s work – is here a gateway to anxiety). It’s tough to do justice to a film like this in this setting. I look forward to writing a more extensive review…

Takeshis’ (Takeshi Kitano)

Takeshis’ (Takeshi Kitano) 81 - There’s a term among anime fans used when the creators of a program insert gratuitous references for the most ardent viewers of a show called “fan service”. Takeshis’ Japanese director Takeshi Kitano’s latest, most playful, and possibly best film is essentially his “fan service” movie. In it Kitano, who has always had something of a split screen personality (he’s known by the pseudonym “Beat” Takeshi when he’s credited as an actor, after all), begins to deconstruct his persona by explicitly revisiting the majority of his body of work, while in the guise of a sad sack doppelganger also named Kitano.

Clearly the closing of a chapter in the director’s oeuvre (don't expect more Yakuza films after this), the film examines Kitano’s frustrations and creative process. The way it does it, however, makes comparisons to 8 1/2 less useful than you might think. Playing out as a series of wildly imagined comic vignettes, the movie doesn't wallow in the notion that the artist possesses a tortured soul that he must harness in order to give to the world. Instead, it seems to plunge headlong into that soul, giving us a fantasia of sequences that give perspective into the works that they reference.

That sounds headier than this incredibly funny movie even tries to be, and I'm afraid my tiredness might be getting the better of me already, but this incredible mash-up of Kitano's favorite obsessions and cinematic tricks (I love the associative editing here...) demands to be seen. With a snappier pace than Kitano usually delivers, it finds the director freed from genre and plot, able to deliver a huge chunk of pure cinema for his and our pleasure. The last forty minutes in particular give the impression that Kitano has been unbridled. Featuring several essentially inconsequential shootouts (I think one of Kintano's big goals here is to simply point out that it's pretty damn cathartic to shoot someone that you find annoying... though he's also underlining the moment of connection that the participants in a stand off feel before they start shooting) and a full-blown musical revue, it is a celebration that's almost enough to make Zatoichi's final scene look boring.

Bonus ratings: October 17, 1961 (Alain Tasma) 35

Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (Peter Tscherkassky) 63

Banileue 13 (Pierre Morel) 34

Friday, September 09, 2005

Just ratings for now...

Three Times (Hou Hsiao-hsien) 77

Battle in Heaven (Carlos Reygadas) 60

Two down... fifty-five to go!

50 Ways of Saying Fabulous (Stewart Main) 31 – There’s not much in this New Zealand-set, gay coming-of-age story that makes it worth recommending. It starts out “cute” and stays there for the duration, making you question not only if any real growth in the characters has occurred at all, but also if writer/director Stewart Main has ever spoken to a child in his adult life. Even when it’s approaching sexual frankness or adding physical danger to the mix, it always tidies up afterwards with a coy, juvenile observation that essentially negates what we’ve just watched.

The movie, set in 1975, features two thirteen-year-old protagonists (one a tomboy, the other a latent homosexual), but to compare it to a movie like Thirteen suggests that it’s studying a different species entirely. That movie had a real sense of danger in its scenes of seduction. This is so consistently twee that it fails to convince as a character study. There’s an entire subgenre of movies like this one, and it seems like the most successful of them are so grounded in specificity and so well-observed that you can’t help but accept them as something honest and true. Despite Fabulous’ inescapably unique setting (it’s set on a farm during a drought), everything about it feels perfunctory. It’s too concerned with plot for its own good, always laying groundwork for later twists. It trots out secondary characters arbitrarily. The performances seem calculated less to help us understand the character than to stir up audience goodwill. The score alternates between obtrusive oboe and piccolo cues, ensuring we always know what to think.

Gilaneh (Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, Mohsen Abdolvahab) 45 – This one works better in theory than in practice, I’m afraid. The concept is pretty interesting: Its first half takes place during the 1988 bombing of Iran at the hands of Iraq, and then it switches its focus to 2003, where fifteen years later it’s Iraq being bombed at the hands of the United States. The movie should play as impassioned plea from the people of Iran, always seen suffering, but it’s too shallow to feel that important. Focusing on the titular character, who it presents as a somewhat hopeless and endlessly self-sacrificing martyr (she and her son blatantly refuse help from their government at one point), it ends up painting a weak picture of the Iranian people, if it’s meant to be taken as a national allegory.

The first half of the film, in which Gilaneh and her daughter travel to Tehran while it’s under siege, is a setup for disappointment. While watching it, I couldn’t help but be aware of the fact that the obviously limited resources of Iranian films would prevent us from ever seeing the war-torn capital. At one point, a woman graphically describes an instance where she saw a children’s hospital as it was bombed. Her verbal depiction of a child, still trying to suckle its dead mother’s breast, is haunting, but you can’t help but crave that visual. Unfortunately, such elaborateness is not within the movie’s means. Creative sound editing, graphic news footage, and the use of off-screen space help somewhat to relay the horrors that country is facing, but it’s too little to pack the punch that’s needed. The second part, which turns the movie into a chamber drama is less satisfying still, with the lead performance slipping into caricature, and the Iraqi conflict being too distant to have any emotional real impact (The characters experience the war on television, like the majority of the world.). It’s a noble movie. I just wish it were a better one.

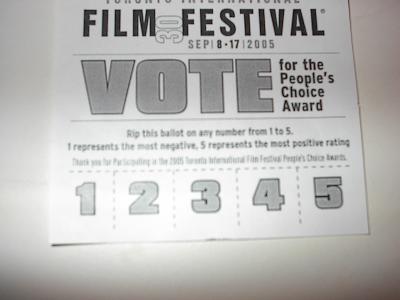

One Interesting Change...

Now you get to vote for every film that you see, which makes more sense than the old system, where you could only nominate one film for the whole fest.

The Tribeca Fest uses this same system, and it's pretty satisfying to give something you hated a "1" or something you loved a "5" as you angrily / elatedly leave the theater. It's instant gratification that can't be denied.

Of course something like Whale Rider has won the audience at both fests, under the different systems, so it probably won't result in a dramatically different winner, but at least this way seems more fair.

Someone, please print me a few hundred of these, and I'll see what I can do about getting Drawing Restraint 9 the audience award. :)

Thursday, September 08, 2005

Dodged A Bullet

Wednesday, September 07, 2005

Screened Pre-Fest

Shanghai Dreams (Wang Xiaoshuai) 59 – A surprise prize-winner at

It stumbles somewhat in its last half-hour, when the script starts working through a series of tragedies that feel just a bit too directly related to the thematic material at hand to be wholly affecting. Overall, though, this is a solid work, filled with elegant master shots and a vivid sense of place.

The President’s Last Bang (Im Sang-soo) 56 – This is a completely capable political satire. Focusing on the real-life 1979 assassination of Korean President Park Chung Hee, it’s irreverent enough to prompt comparisons to Dr. Strangelove, and I imagine that for Korean audiences it might be as shocking as that film would have been back in the ‘60s. In the interest of full disclosure, I suppose I should point out that I don’t consider Kubrick’s film to be the masterpiece it’s generally touted as, but those who do can believe the hype surrounding this one. They will likely consider Last Bang to be of the year’s very best films.

Im’s take-no-prisoners approach starts out jokey, but when the shit finally goes down, and the balance of power shifts, the film reveals a surprisingly fierce political perspective. Oscillating between jet-black humor and severe contempt for Park’s regime, the movie shifts tones with an adeptness that seems innate to the new Korean Cinema. The wide-ranging series of perspectives we see, ensures that no party is left uncriticized, and the film is formally excellent, filled with elaborate tracking shots, and tableaux framings that imply how removed from reality the administration is. All in all, it’s an undeniably well-made film that I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend, despite my personal predilections.

More TIFF Links

Doug Cummings at filmjourney.org

Mike D'Angelo's The Man Who Viewed Too Much

Steve Erickson's Chronicle of a Passion

Darren Hughes' Long Pauses

Victor Morton, Rightwing film geek

Charles Odell's Chateau Du Cinema

Dan Sallitt is reporting on the fest for Senses of Cinema.

Michael Sicinski is The Academic Hack

I didn't realize Scott Tobias was TIFFing this year until I ran into him there.

GreenCine Daily is bound to have a few more worthwhile links.

Edited to add:

Chris Nolan's TIFF Blog

Mathew's Film Festival Journal

Sean P. Kelly on Movies

http://blogs.indiewire.com/toronto/

Filmnerd3

The GATE Festival Blog

Twitch

Movie City News' Festival Blog

Jeffrey Wells' Hollywood Elsewhere

If I've missed anyone, let me know...

Finalized Schedule

Most likely, this is the plan:

9/8

50 Ways of Saying Fabulous Stewart Main

Gilaneh Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, Mohsen Abdolvahab

9/9

Takeshis' Takeshi Kitano

Three Times Hou Hsaio-hsien

Battle in Heaven Carlos Reygadas

October 17, 1961 Alain Tasma

Wavelengths: Program 1 Various

Banlieue 13 Pierre Morel

9/10

Be With Me Eric Khoo

L' Enfer Danis Tanovic

Linda Linda Linda Nobuhiro Yamashita

Sunflower Zhang Yang

Sa-kwa Kang Yi-Kwan

Evil Aliens Jake West

9/11

Thank You For Smoking Jason Reitman

3 Needles Thom Fitzgerald

Manderlay Lars von Trier

The Forsaken Land Vimukthi Jayasundara

Mary Abel Ferrara

Isolation Billy O'Brien

9/12

The Quiet Jamie Babbit

Revolver Guy Ritchie

Cache Michael Haneke

Wassup Rockers Larry Clark

River Queen Vincent Ward

Bangkok Loco Pornchai Hongrattanaporn

9/13

Harsh Times David Ayer

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada Tommy Lee Jones

Backstage Emmanuelle Bercot

Why We Fight Eugene Jarecki

Duelist Lee Myung-se

9/14

Walk the Line James Mangold

Tideland Terry Gilliam

Festival Annie Griffin

Fateless Lájos Koltai

Iron Island Mohammad Rasoulof

9/15

The Porcelain Doll Péter Gárdos

Romance & Cigarettes John Turturro

Look Both Ways Sarah Watt

Free Zone Amos Gitaï

Runaway Tim McCann

Angel Jim McKay

The Great Yokai War Takashi Miike

9/16

Un Couple Parfait Nobuhiro Suwa

Vers Le Sud Laurent Cantet

Everlasting Regret Stanley Kwan

The Notorious Bettie Page Mary Harron

Entre ses mains Anne Fontaine

Brothers of the Head Keith Fulton, Louis Pepe

SPL Wilson Yip

9/17

Le Temps qui reste François Ozon

Citizen Dog Wisit Sasanatieng

Drawing Restraint 9 Matthew Barney

U-Carmen eKhayelitsha Mark Dornford-May

Wah-Wah Richard E. Grant

Hostel Eli Roth

Sunday, September 04, 2005

Speaking of worst-case scenarios:

It also premiered today at Venice. The reviews haven't hit yet, but here are some pictures of Bjork & Barney on the red carpet.

Wow, I am spoiled...

Of course, I'll be able to see the other 50-something movies that I planned on seeing, so I'll try to look on the upside of things... It certainly could have been worse.